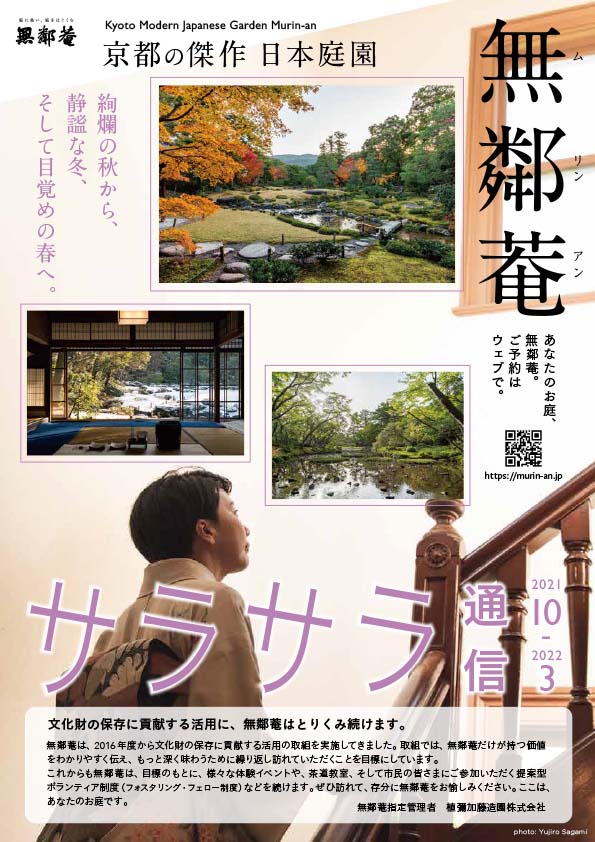

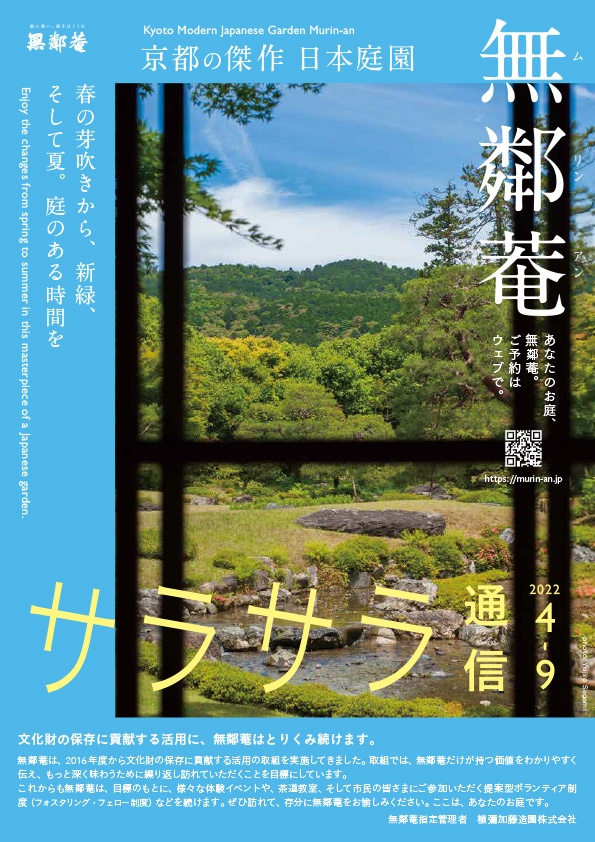

Connect with yourself from a time gone by.

Encounter a future where you no longer exist.

When we transcend our present-day sense of time, a world of freedom becomes visible.

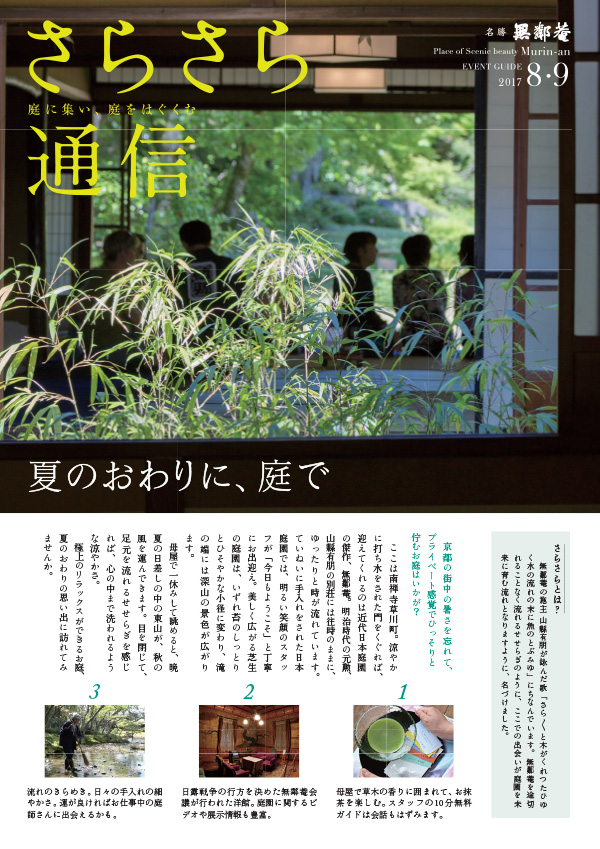

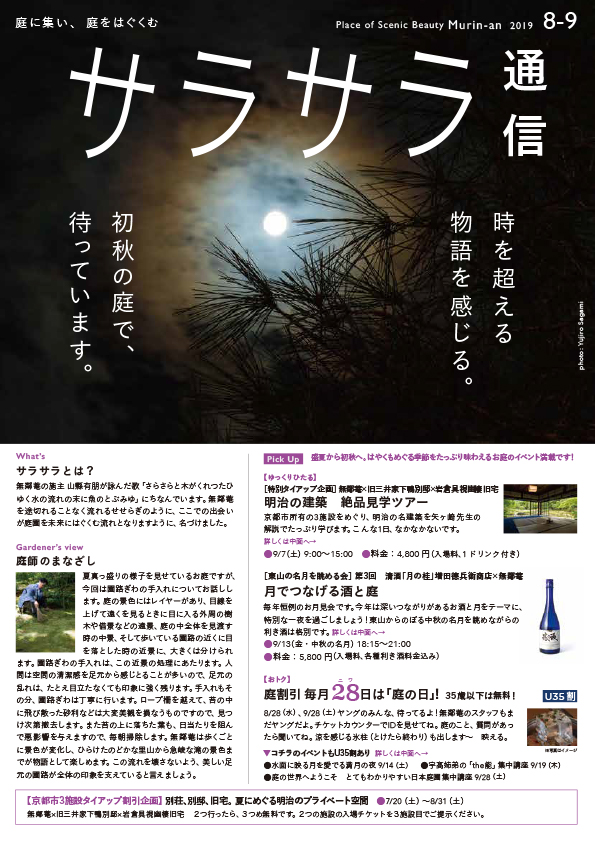

Sara-sara Mini 2019, Aug-Sept

Q. What are your dreams and goals as a Noh performer?

I hope to achieve a position where I can communicate Noh technique by becoming able to imagine how, in a world where I no longer exist, the next generation can take that technique even further. By the way, in the world of Noh, the word “dream” has a different meaning from that of “goal.” It has a strong sense of the impermanence witnessed in words such as “forlornness,” “all ends with death,” or “you can’t take it with you.” That feels like a real downer, but it isn’t entirely negative; to the contrary, it also has a therapeutic effect.

Q. Impermanence has a therapeutic effect?

Yes. As it is spoken of in contemporary society, I think that the word “dream” already has a certain image of success associated with it, like the word “goal” we just discussed, and that there is always some model pointing it in that direction. Just like when a goal is predetermined to be 100 points. To go even further, it is transparently evident that these words contain fixed notions such as everyone must be happy or one must absolutely be successful. Perhaps you could call it a state of forced tension. In Noh, on the other hand, dreams have a vector that expands our eyes toward phenomena other than our contemporary selves. This includes imagining the world after you have died, or reconceiving of a self from the past as a different person. The Japanese cartoon character Doraemon also sometimes goes to meet himself from the past, and I think this is incredibly Noh. When you’re a little tired, try imagining your time not just as pointed straight toward the future, but a different time flowing toward the past, other people and different places. It will relax you a little.

Q. Is imagining a different time something you do on the stage as well?

One of the sayings of Zeami, who perfected Noh theater, is “the view separated from one’s view” (riken no ken). It means that it is important to separate from oneself performing on the stage and to see oneself from the position of the audience. It doesn’t mean its sufficient to just take a video of yourself, but rather keeping the audience’s perspective within you while you perform. My thought is that this isn’t something just limited to a performance that is bound within a single period of time. I think that imagining the world after you die or a time before you were born are also “views separated from one’s view.”

Q. The ultimate power of imagination!

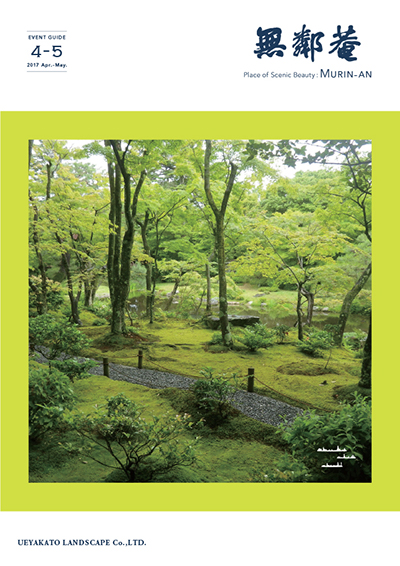

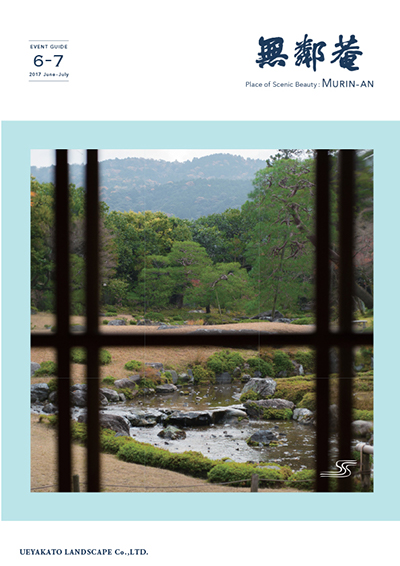

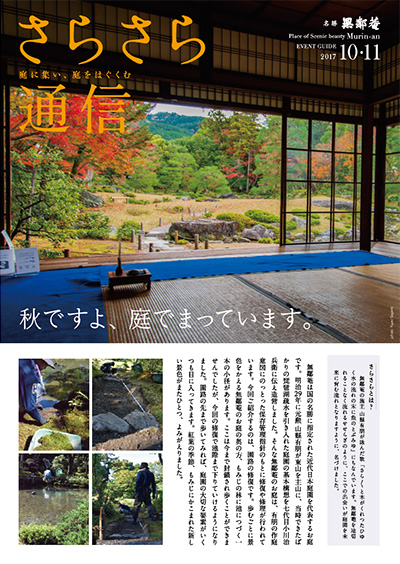

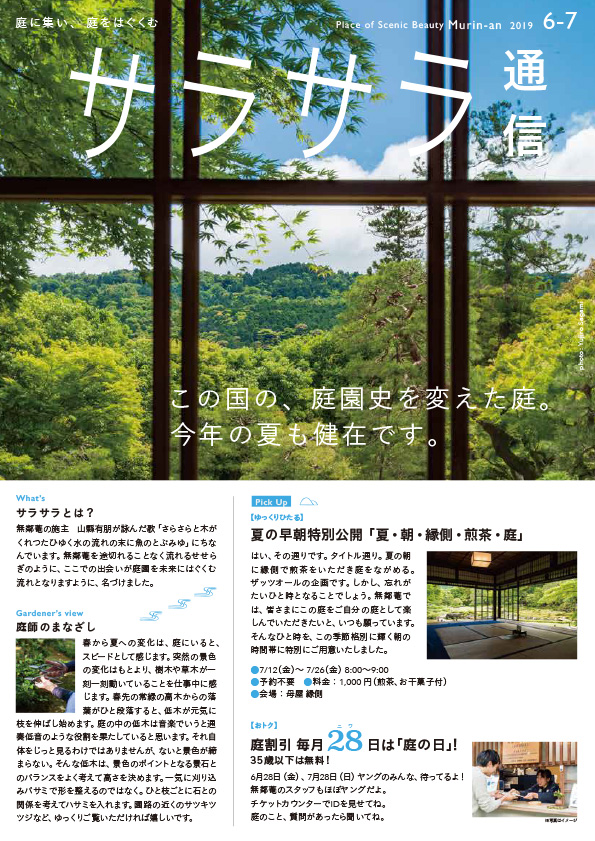

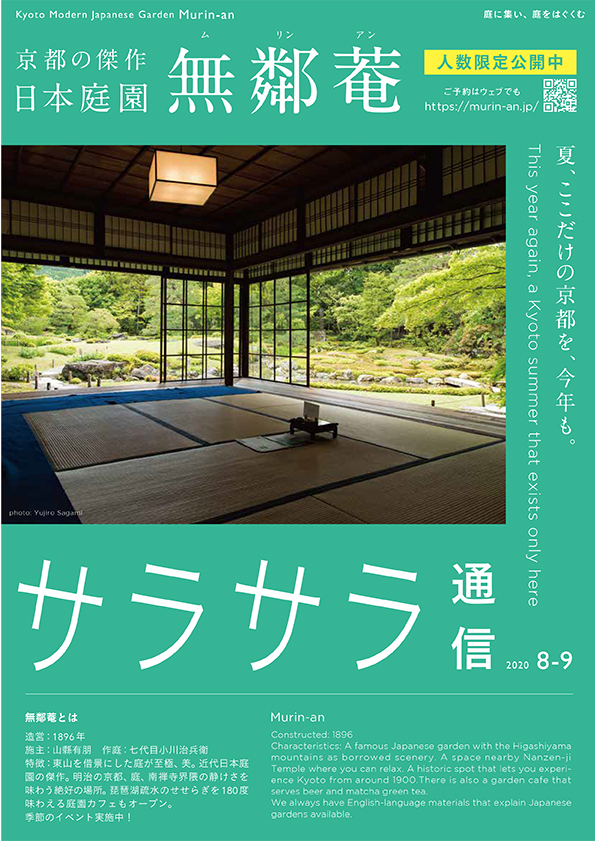

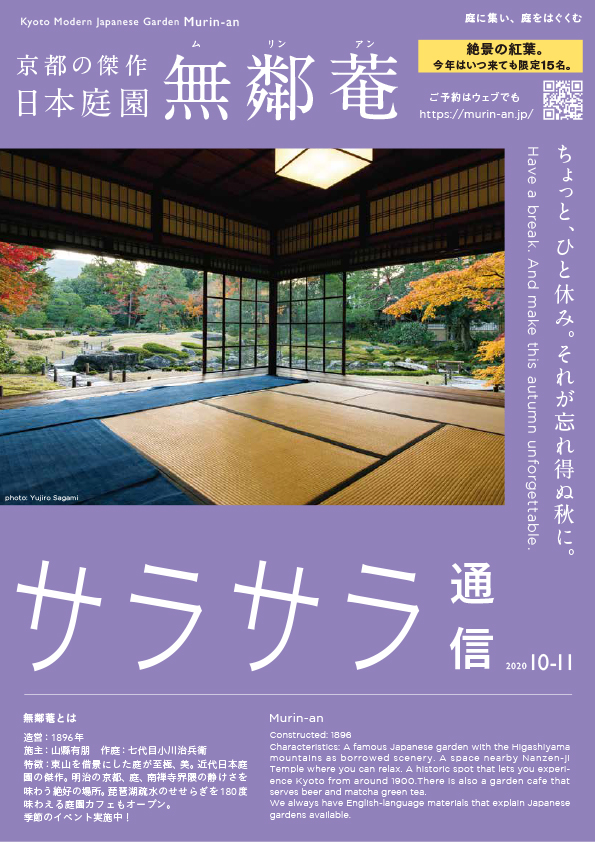

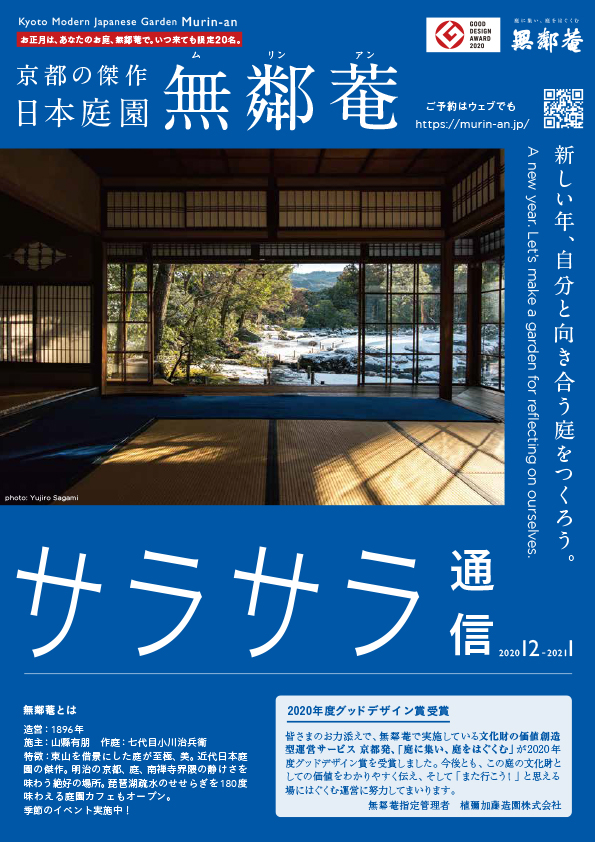

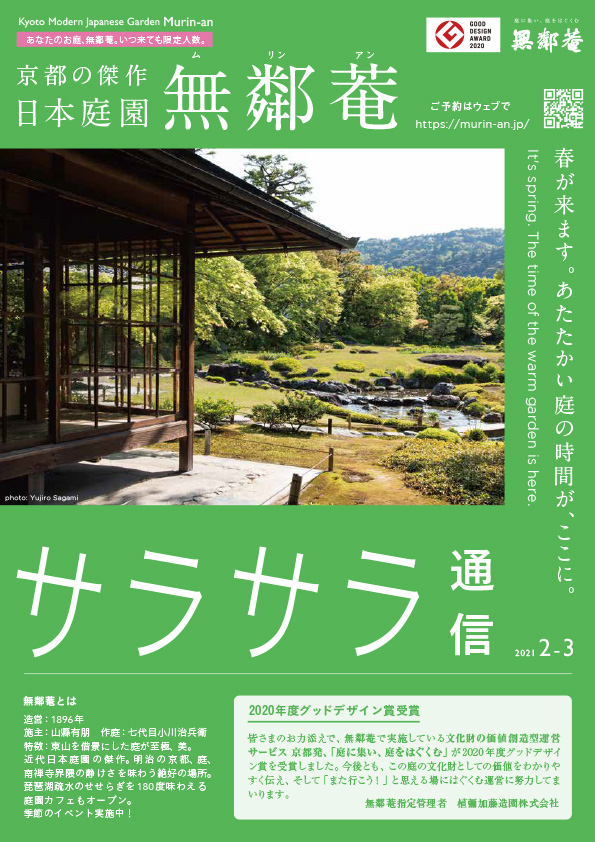

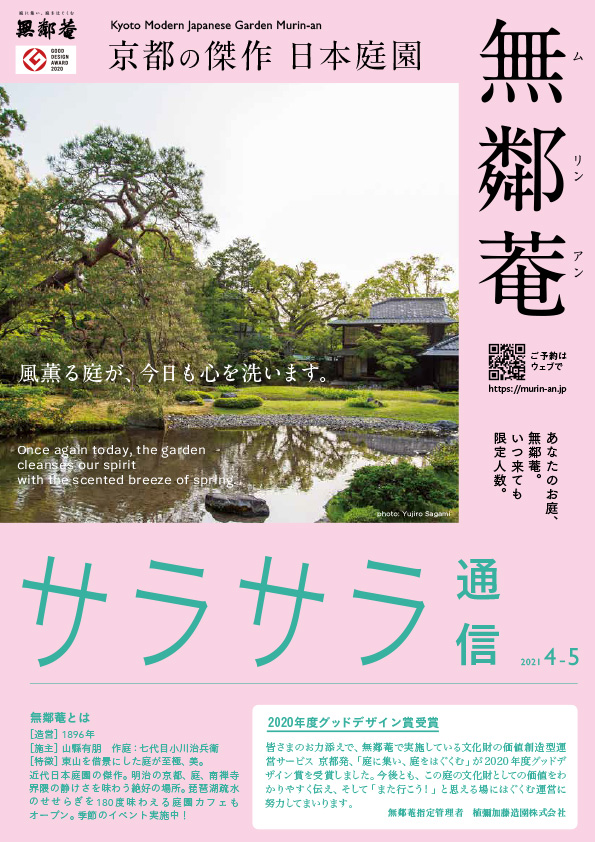

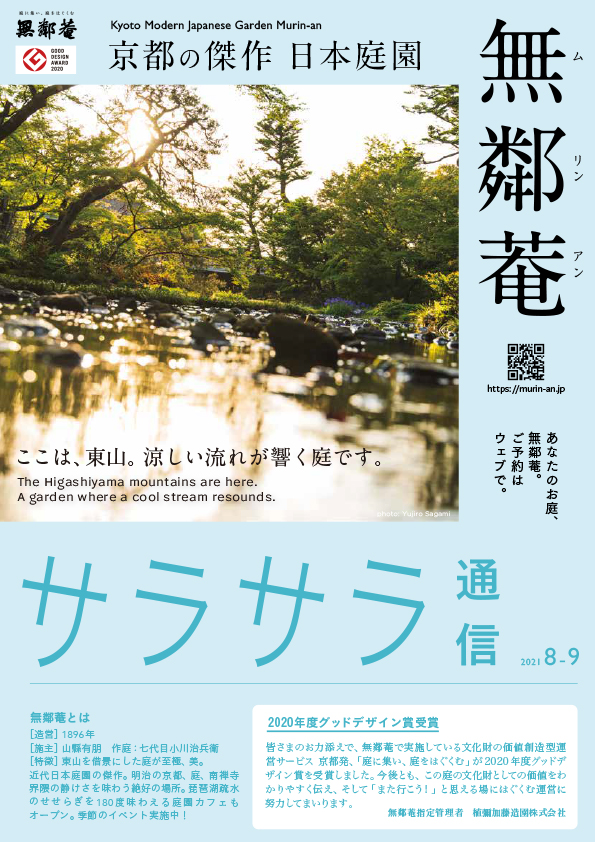

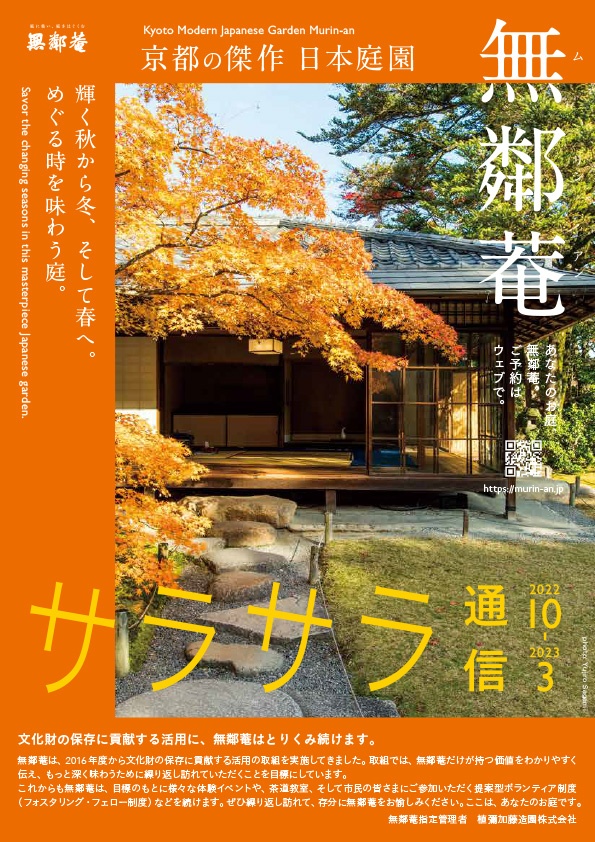

Perhaps. But wasn’t that also the case for Yamagata Aritomo, who created this garden called Murin-an? When Aritomo incorporated into his garden the Kusakawa area and the Higashiyama mountains, which existed before he created Murin-an, I think he surely must have imagined things in terms that transcended time and space. Thought of in this way, there is really almost nothing in this world that can be said to belong to oneself alone. Thinking about how the contemporary self is connected to things besides oneself leads to ease of mind and is also a source of being creative. To stand on the Noh stage also means to continue losing every day the kata (movement pattern form) that one has attained. It is akin to gaining a new kata for a self that is continually changing day by day. It is also painful sometimes, but I believe that that something is created at such times by imagining a different time.

The Udaka family’s intensive seminar “the Noh” begins on September 19 (Thurs.), 7:00 PM!

Discounts for all aged 35 or younger.